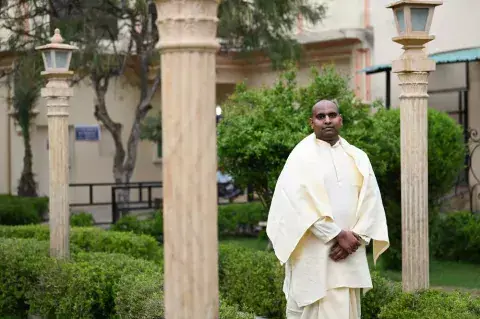

Yudhistir Govinda Das represents the Gaudiya Vaishnava tradition, whose core beliefs are based on sacred Hindu texts. From early childhood, he knew that he would devote his life to the community of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness. The sole question was whether his lifelong devotion to the cause would be as a monk or as a community member.

“In terms of my personal and spiritual goals, it was always clear that I needed to do something for God and for the community.”

Growing up during India’s oscillating periods of peace and conflict, the need to focus on reconciliation and healing quickly crystallised in Yudhistir’s young mind. Today, as an adult, he believes more than ever that there is a major need for interreligious dialogue within the massive South Asian nation.

The rise of fake news coupled with problematic and offensive opinion, much of it proliferated via social media, has become a key incubator of resentment, pushing people towards violence among parts of India’s Christian, Hindu and Muslim communities.

“I wouldn’t say that it has spread all over the country, but certainly, in some parts of India it’s very prominent. That’s where we, as peacebuilders and interreligious dialogue practitioners, have an important role to play.”

This drive to solve the problems facing India has inspired Yudhistir to look at the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that provide a series of targets to help countries to eliminate poverty, improve healthcare and education, reduce inequality, spur economic growth and tackle climate change by the year 2030. Yudhistir has assessed the role that faith communities, in particular, can play in the achievement of the goals.

“The United Nations consulted policymakers and business communities on the SDGs, but not faith communities,” he said.

Given that, according to Pew Research, over 80% of the global population identies with a religion, Yudhistir felt driven to reach out to current Indian KAICIID Fellows and alumni, as well as to senior Indian faith leaders and policymakers, to talk about how the faith community can have a voice in the SDG discourse. As a result of the talks, a conference on inclusive education (SDG4), gender equality (SDG 5) and peaceful communities (SDG 6) has been scheduled to take place in Delhi during the summer of 2020.

Alongside his passion for the SDGs, Yudhistir is keen to be an expert on interreligious dialogue. Having found a paucity of local dialogue training opportunities in India, he sought out the Fellows programme. He was also inspired, in part, by the findings of John Fahy’s paper, Beyond Dialogue? Interfaith Engagement In Delhi, Doha & London, which asserts that a reluctance to address social issues around religious dierences leads some of the participants in dialogue initiatives to perceive the dialogue space as an echo chamber in which disagreements are eschewed, and from which, therefore, no real outcomes can emerge.

Yet, even if some of India’s dialogical spaces do not allow for disagreement, discord and violence are nevertheless happening at grassroots levels in some remote villages, according to Yudhistir, “An Indian can watch a video online, of something that possibly happened in Syria, and be convinced of it having happened in a neighbouring village. Then he is ready to attack his neighbour. How do you resolve that? That’s the real challenge,” he said.

Looking ahead, the challenge is not to coalesce communities around the idea that it is important to help followers of different faiths understand one another.

“Instead, the challenge lies in creating and managing a structured entity with intellectually robust programming, that can offer sustainable dialogue initiatives,” he said.

This structured entity is what Yudhistir is working on, not only with other members of the Fellows programme, but also through his extensive and influential network of lawyers, policymakers, think-tank executives, social activists and religious leaders. The task is not a simple one because, as well as the need to differentiate new interreligious dialogue bodies in an already crowded space, there is a level of cynicism that Yudhistir and his colleagues need to overcome.

For instance, it is apparent that some new interreligious initiatives are perceived with a degree of scepticism in India, by people wary of proselytisation or of ambiguous intentions among some of the dialogue actors. Yet, even in the face of this distrust, Yudhistir’s optimism persists.

He is working hard to recreate the global KAICIID Fellows network in India in order to establish a scalable nationwide resource that bridges gaps in religious understanding among and between Christian, Hindu, Muslim and Vaishanava communities. As ambitious as his goal is, Yudhistir’s aspirations, together with those of the other Indian Fellows, are reinforced with realism.

“We’re not saying that we’re going to resolve every issue. We’re trying to create bridges between communities so that at least there is an open channel and dialogue can happen such that, if a conict erupts, there is a partner on the other side.”

This Piece is part of a larger series on Five Years of the Fellows Programme. Read more here.